This is a very silly start to this blog, but I do get to the 1949 trip later in the blog.

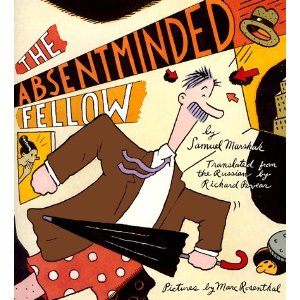

In one of Charles (Prendergast’s) favorite books from his childhood, The Absent-Minded Fellow from Portobello, the eponymous protagonist attempts–in vain–to get from his flat in Portobello to London. While there is no specific date for the events in the book, the illustrations harken back to 40’s and 50’s London.

Based on this book, it’s surprising that our travelers made it to London at all, given the many obstacles that occur to someone just trying to get from Portobello to London. Our protagonist can’t see at first because he has put his pants on his head, then, misunderstanding a porter’s directions he jumps into a train car that is not actually going any place. In the middle of the book, the incantatory phrase “London, London, London” appears. Given the number of times that I read that book out loud to Charles (usually slowly and gently closing his eyes as he listened), I can’t think of London without considering it as three words.

I am not alone. I Googled “London, London, London” and came up with a song sung by Fergie about London Bridge. It goes something like this: Oh snap! Oh snap! Oh snap! (Are you ready for this?) Oh snap! In-between are the usual naughty–but not too naughty–words by Fergie like “pimp”, then we get to the following:

How come every time you come around

My London London bridge, wanna go down like

London, London, London, wanna go down like

London, London, London, we goin’ down like

I’m not really into Fergie music, but I do like this one.

So London bridge is now a reference to dancing and sex–most likely not the first time a bridge has been used in the latter reference.

The Kinks also write about London hypnotically:

When I think of all the londoners still unsungEast-enders, west-enders, oriental-endersFu manchu, sherlock holmes, jack spock, henry cooper,Thomas a’becket, thomas moore, and don’t forget the kray twinsThere’s a part of me that says get outThen one day I’ll hear somebody shoutSounds to me like you come from london townBut if you’re ever up on highgate hill on a clear day,I’ll be there [I’ll be there]Yes I will be there [there]Through the dark alley-ways and passages of london, londonLondon, london, through the dark alley-ways and passages of london, londonLondon, london, through the dark alley-ways and passages of london, london.

And the hip-hop singer Kano has a song whose only non-explicit verse is:

London, London, London town

You can toughen up or get thrown around.

The point is that there is something marvelous and hypnotic about the idea, and even the sound, of “London”, a place that incantatorily draws people to it, even as it maintains its reputation for sootiness, thuggishness, and strange things around the corner. After all, people are drawn to London as much because of Jack the Ripper and its (no longer existing) pea soup fog as they are to its royal family, high tea, and Harrod’s. And, anyway, the phrase “London, London, London” also shapes a nice trochaic trimeter that fits the short, insistent beat of hip hop particularly well.

I’ll stop here, I promise, because it is time to talk about Harrod’s.

* * *

In 1949, London was the place to start for most American tourists–because they could speak the language, and because it was already so familiar to them from books, History classes, and film, and because of the large number (relatively) of flights there.

It’s no surprise, then, that this is where our travelers decided to start. It’s also probably no coincidence that they stayed in England for slightly less than a month. According to Joseph Frayman, anyone staying for longer than twenty-eight consecutive days in Britain was required to get a visa (NYT Mar 6 1949).

The London our travelers encountered was, despite the reduction of the pound, a place of optimism. New York Times articles from 1949 record an upswing in production activity for London film studios and a removal of most rationing. The Treasury’s “Economic Survey for 1949” “showed that Britain had almost achieved an overall balance of trade with the rest of the world” (NYT Mar 20, 1949). And, despite continued rationing of ham, bacon, cheese, butter, margarine, meat, sugar, and tea, John Strachey, British Minister of Food, “recently made the surprising statement–so surprising that he said most people wouldn’t believe it–that Britain’s current average daily ration is only ten calories below that of the pre-war days–2,990 calories as against 3,000” (NYT Mar 29, 1949).

And for Anisa, London seems to have been about Harrod’s.

For some reason, the only thing my mother really remembers about Harrod’s is that Anisa bought some shoes there; here is her rendition of the results of that shopping expedition:

Anissa: “Look at the shoes I got at Harrod’s! Because I’m a foreigner, I don’t need a ration card to buy shoes.”

Carmen: “Maybe we could buy things for other people because we don’t need ration cards.” Maria’s added comment: “Mother right away found the loophole for things.”

What London did not Have

London did not have good food, or, at least, the good food was not easy to find, except for the lovely fruits and vegetables one kept coming across at the market. The Rembrandt Hotel did have a nice breakfast, if one could take the smell of kippers, and a good breakfast there sustained the travelers for most of the day. But what to do about dinner time?

It was late in the trip, after many unsuccessful attempts at a decent dinner that they discovered the Indian restaurants, which had the best food in India. That, and a memorably deliciously restaurant splurge at the Barclay Hotel, “on that street across from Fortnum and Mason.”

Arriving at a city eager for American dollars, the travelers embraced tourism enthusiastically–thanks, in part, to an apparently restful stay at the Rembrandt Hotel–the subject of my next blog.

Speak Your Mind